By Victor V Rao MBBS, DMRD, RDMS

Introduction

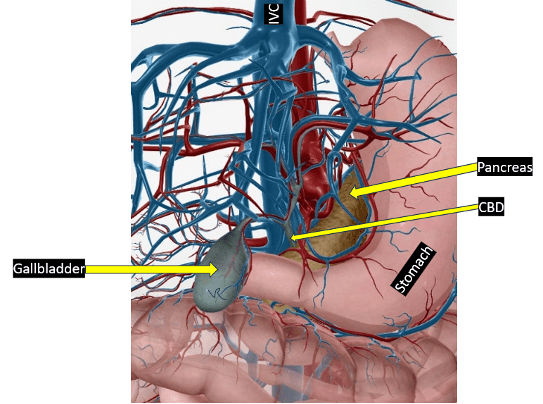

The gallbladder (GB) ultrasound examination can be challenging at times due to patient body habitus or bowel gas. With proper patient preparation and correct technique, the gallbladder ultrasound can be performed successfully. Gallstones are quite commonly encountered while performing an ultrasound examination of the abdomen. Gallstones are generally seen within the lumen of the gallbladder and sometimes within the common bile duct (CBD). However, at times the patient may present with a history of right upper quadrant (RUQ) pain with nausea and vomiting and even a long history of intolerance to fatty food.

The advantage of POCUS gallbladder assessment is that you can easily image the gallbladder and detect gallstones, sludge, polyp or mass, gallbladder wall thickening and pericholecystic fluid in case of acute cholecystitis and even sloughing of the inner layer of the gallbladder due to gangrenous cholecystitis or emphysematous cholecystitis with presence of echogenic air pockets within the gallbladder. The latter two are life threatening conditions and must undergo immediate surgical management to avoid possibility of serious complications, septicemia and death.

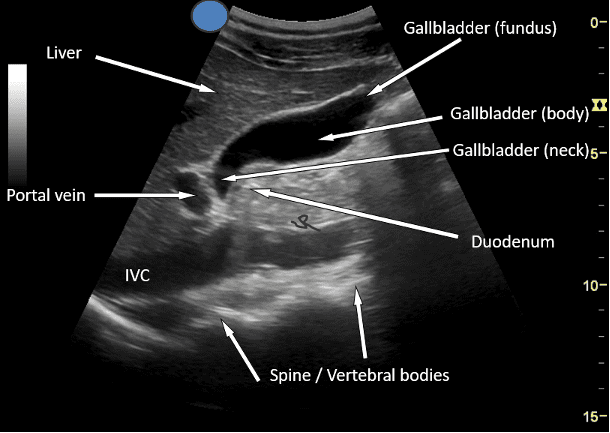

Figure 1. Gallbladder and surrounding structures. The liver has been removed to show the gallbladder clearly.

Common Signs and Symptoms

Even though a patient with gallstones can be to totally asymptomatic, the patient may present with the following:

- Abdominal pain (typically right upper quadrant)

- Intermittent abdominal pain

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Fever+

- Dark colored urine and yellowish color of skin or conjunctiva (only if obstructive jaundice)

Role of Ultrasound as a Diagnostic Tool

Ultrasound is considered the first imaging modality of choice to assess the gallbladder, biliary tree, and associated ducts such as the common bile duct (CBD) for the presence of gallstones. Ideally the patient should be scanned using a low frequency curvilinear transducer or a low frequency transducer to image the gallbladder and surrounding anatomy. If the gallbladder happens to be very superficial and close to the skin surface, you may also obtain some high-resolution images using a high frequency transducer.

It is important that the patient is fasting before the examination. This can work for an elective ultrasound examination. Sometimes the patient may present acutely in the emergency department with right upper quadrant pain and the gallbladder may or may not be adequately visualized as the patient may not be fasting.

How to Perform the ultrasound Examination

Scan with the patient in the supine position. It is also advisable to scan the gallbladder in the left lateral decubitus and upright position if there is a high suspicion of a gallstone. If the gallbladder is contracted, then it is recommended to perform a repeat ultrasound with the patient fasting. Be aware that the fundus and body of the gallbladder are freely mobile and may change position with change in patient position during the ultrasound examination. However, the neck of the gallbladder is fixed in location and can be seen next to the hyperechoic main lobar fissure of the liver.

Figure 2. Anatomy of the gallbladder. Impression: Normal gallbladder

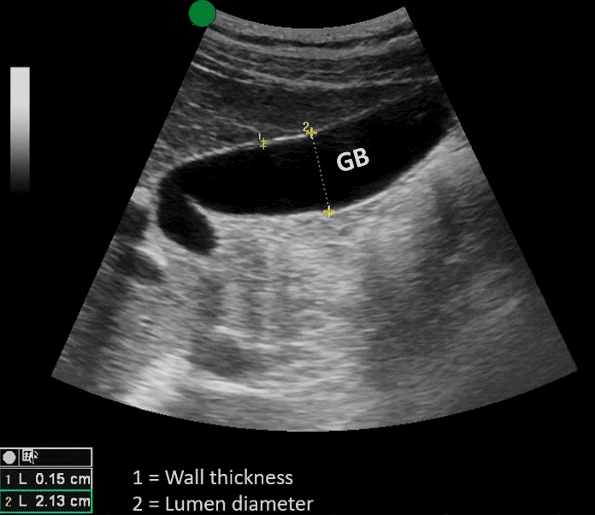

How to Measure Gallbladder Wall Thickness using B-mode ultrasound

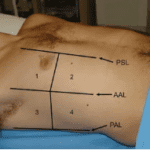

Measure the wall of the gallbladder as shown. Measure the wall of the gallbladder closest to the anterior abdominal wall in the region of the liver anteriorly and the bile filled lumen of the gallbladder posteriorly. We do not measure the posterior wall as it may not be clearly defined as seen in the image. Be aware that other conditions such as ascites, renal failure, and right heart failure and a contracted gallbladder (post prandial) can make the gallbladder wall appear thickened and does not suggest acute cholecystitis. Always correlate clinically.

Figure 3. Mid-longitudinal view of the gallbladder. The gallbladder is adequately distended. No mass, polyp, stone, or sludge seen within the lumen of the gallbladder. Normal gallbladder wall thickness should be less than 3 mm in a well distended gallbladder. In this case the gallbladder wall thickness is 0.15 cm (1.5 mm) #1. The gallbladder wall is not thickened. No pericholecystic fluid seen. Impression: Normal gallbladder.

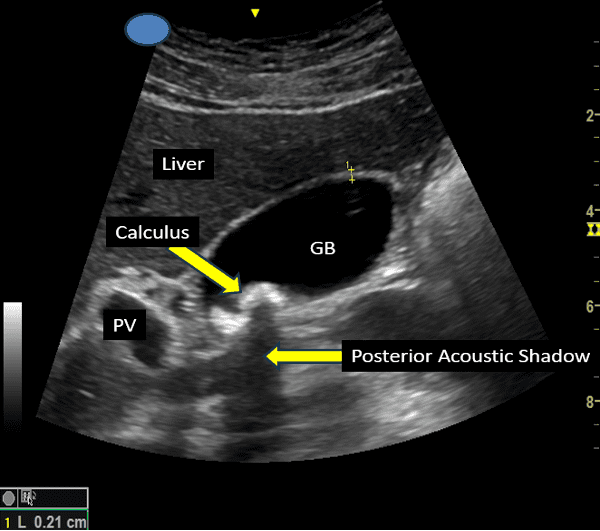

Figure 4. Cholelithiasis. Note that the gallbladder wall is not thickened (< 3 mm). Final Impression: Cholelithiasis. No evidence of cholecystitis.

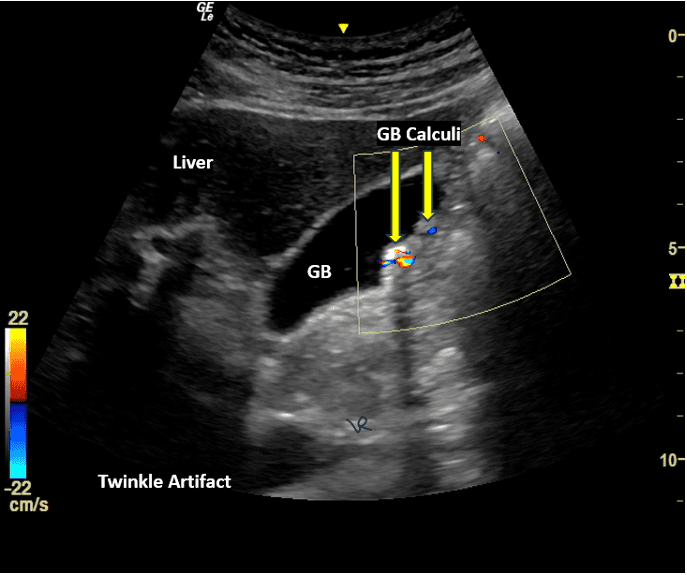

Figure 5. Multiple gallstones within the lumen of the gallbladder eliciting twinkling artifact in color Doppler mode. Posterior acoustic shadow is also seen posterior to one calculus.

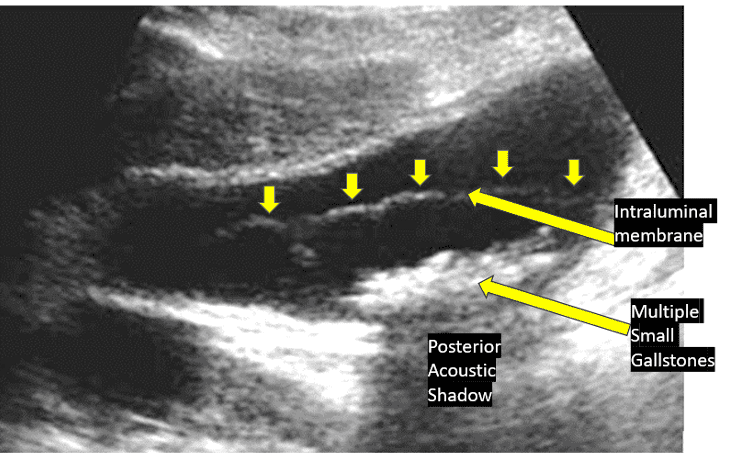

Figure 6. Distended gallbladder with multiple small stones and a membrane like structure in the lumen of the gallbladder. Impression: Cholelithiasis and gangrenous cholecystitis. Do not be distracted by gallstones. Gallstones are not life threatening but gangrenous cholecystitis is life threatening and requires urgent surgery.

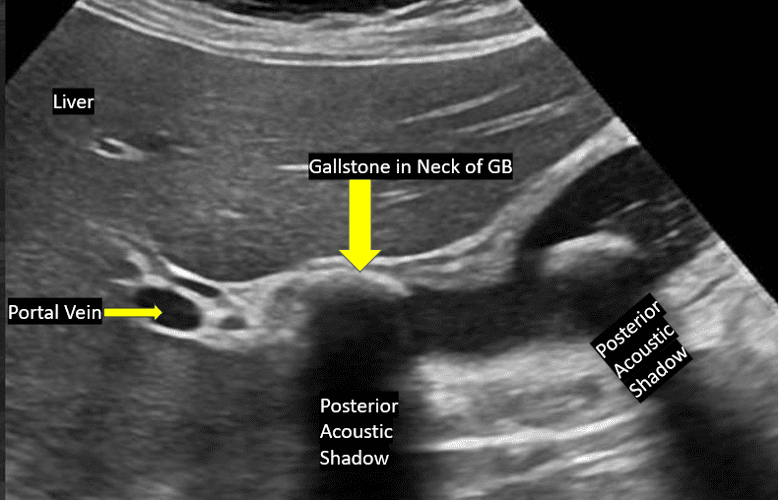

Figure 7. Gallbladder with two gallstones. One stone is seen in the region of the neck of the gallbladder. This is known as the Stone-in- Neck (SIN) sign. The SIN sign is considered as a sign of cholecystitis. The stone should be immobile and should not move when the patient is rolled to the left lateral decubitus position or made to sit up in the upright position. There should be no anechoic space (bile) in the space between the stone and either wall of the gallbladder. Look carefully at the image. There is no anechoic space due to the presence of bile between the stone and the wall of the gallbladder. You see a hypoechoic region which is the edematous gallbladder wall. Final Impression: Cholelithiasis + SIN sign positive (acute Cholecystitis).

Final Thoughts

Gallbladder ultrasound can be challenging at times. It is important to have the patient prepare for the ultrasound examination by fasting overnight and be on a fat-free diet for a couple of days for the best results. With proper preparation and correct imaging technique the pooled sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing gallstones was reported to be 0.94 and 0.93 respectively with a high confidence interval of 95%.

In an emergency, we must scan the patient without any preparation. Be sure to examine the gallbladder with the patient in different positions and fanning the transducer though the entire gallbladder and beyond to avoid missing small lesions and even small gallstones. I was surprised to see a normal gallbladder with no gallstone detected in the supine position and when the patient was rolled to the left lateral decubitus position, a small calculus suddenly appeared.

POCUS gallbladder assessment is a great skill to master because the right upper quadrant pain and discomfort is one of the most common presenting symptoms in an outpatient setting. When assessing a patient for possible acute cholecystitis, be aware that the patient may have a negative ultrasound Murphy’s sign if the condition has progressed to gangrenous cholecystitis. The wall of the gallbladder may also be disrupted with local fluid collection or abscess formation. You cannot manage gangrenous cholecystitis and emphysematous cholecystitis medically only. These conditions require immediate surgery as they are life threatening conditions. POCUS gallbladder assessment can make a significant difference in the diagnosis and management of cholelithiasis and the above-mentioned conditions and their management.

References