Author: Mel Ebeling, BS

Introduction

The use of chemical and nuclear weaponry is a growing concern as the Russo-Ukrainian war has progressed this year.1 From a healthcare standpoint, this threat should cause us to evaluate our preparedness for these types of crises, including the need for and use of versatile equipment and processes in consequent mass casualty incidents (MCIs). This is especially relevant for those who would be at the frontlines if such an incident were to occur, particularly emergency medicine physicians and emergency medical service (EMS) providers with the capability to conduct point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS). In this post, we will expand on what chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, and high-yield explosives (CBRNE) events are while providing examples of relevant historical events, discussing applications and considerations for POCUS in those types of situations, and describing educational opportunities for professional development.

What is CBRNE?

CBRNE is an acronym for types of weapons of mass destruction (WMDs), which are deliberately designed and used to “cause death or serious bodily injury,” such as in a terrorist attack, and are capable of causing MCIs and disrupting society on a large scale.2,3 Examples of chemical agents that could be used as a WMD include, but are not limited to, nerve agents (e.g., VX, sarin), vesicants (e.g., sulfur mustard), blood agents (e.g., cyanide), and incapacitating agents (e.g., BZ). Biological agents that could be weaponized not only include bacteria (e.g., anthrax) and viruses (e.g., smallpox) but also toxins, like ricin, which comes from castor beans, and botulinum toxin which is produced by the bacterium, Clostridium botulinum. Radiological materials used in exposure or dispersal devices, Cobalt-60, for example, emit ionizing radiation, meaning that they emit energy with the ability to remove electrons from other atoms or molecules. Fissile materials used in nuclear weapons can also release energy in the form of ionizing radiation. Finally, it should be noted that while explosives alone pose their own inherent threat, they have the potential to be used in combination with the chemical, biological, and radiological materials previously described.

Examples in History

The threat of a CBRNE/WMD incident is not limited to any one country, as incidents have occurred worldwide. In 1995, a doomsday cult called Aum Shinrikyo released sarin gas in a subway in Tokyo, Japan, killing 13 and injuring 5500. In 1984, The Rajneeshees carried out a biological attack in The Dalles, Oregon, when they contaminated salad bars across the town with Salmonella in an attempt to keep people from voting, injuring 751. While the U.S. attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II are still the only examples of nuclear warfare, the threat posed by nuclear weaponry is still ever-present, as mentioned in the introduction. Similarly, a threat still exists for the use of radiation dispersal devices (e.g., “dirty bombs”), despite there not yet being any reported incidents. CBRNE/WMD incidents of the explosive variety include, for example, the Boston Marathon bombings in 2013 and the London bombings in 2005. Interested individuals may explore the Global Terrorism Database for more information on acts of terrorism.

Although it seems intuitive, it is important to emphasize that mass casualties are a primary consequence of CBRNE/WMD incidents, and critical infrastructure may also be impacted. Even with proper planning, EMS and hospitals can become overloaded with victims and “worried well” and lack the necessary supplies, equipment, and personnel to mitigate such a situation.

Applications, Considerations, and Advantages of POCUS in CBRNE Incidents

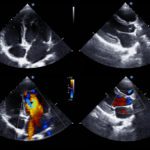

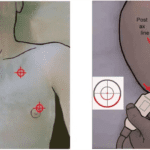

Patient triage is a primary application of POCUS in a CBRNE/WMD-caused MCI. In incidents involving explosives, the Focused Assessment with Sonography in Trauma (FAST) exam can rapidly triage patients who may have suffered from primary, secondary, and tertiary blast injuries (e.g., abdominal perforation and hemorrhage). In fact, this capability has already been employed in multiple major bombings.4 Interestingly, two companies have even partnered to develop an ultrasound-based device that can be deployed in a CBRNE event for rapid fracture detection and triage.

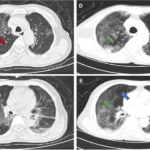

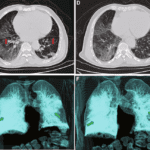

For CBRNE/WMD incidents involving chemical agents, POCUS could be used to evaluate and triage for hemorrhagic pulmonary edema or acute respiratory distress syndrome secondary to vesicant-induced pulmonary injury.5 Outside of triage, POCUS may still be used procedurally to manage patients affected by a CBRNE WMD, such as performing a thoracentesis for a pleural effusion arising secondary to infection with a viral hemorrhagic fever.

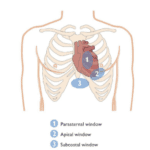

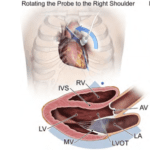

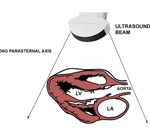

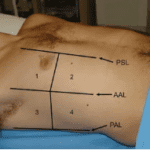

Regardless of the application, it is essential to remember that in an MCI involving chemical, biological, or radiological material, there is a special need for personal protective equipment (PPE) to protect first responders and emergency department personnel against cross-contamination. Unfortunately, PPE specific to these hazards may preclude patient assessment through more traditional methods. Listening to a patient’s lungs with a standard stethoscope may be impossible if the provider is wearing a hooded respirator. Along the same lines, trying to feel for pulses through several layers of gloves may be unfeasible. In the first example, POCUS could be used instead to evaluate for a potential pneumothorax when a provider is unable to auscultate for an absence of breath sounds. Moreover, POCUS could provide a visual image of the heart rate through a cardiac window in the second example.

It is important to remember that even though x-ray imaging or computed tomography scans may be better modalities for a particular disease process under normal operating conditions, hospital radiology departments are bottleneck points in MCIs, making the speed and portability of POCUS highly advantageous.6 In addition to the portability that handheld POCUS machines possess, allowing them to be brought to any area of the hospital or out in the field, they are easy to operate and may prove to be easily manipulatable while wearing dexterity-impairing PPE. Finally, the availability of transducer probe covers may facilitate the decontamination process, preventing possible cross-contamination between patients and increase the speed at which patients can be assessed.

Resources/Training

To prepare for CBRNE/WMD MCIs, becoming proficient in emergency medicine POCUS is encouraged. Alongside traditional textbooks like Ma & Mateer’s Emergency Ultrasound, individuals can check out the POCUS Education Provider (PEP) program for professional ultrasound courses. Emergency responders and healthcare providers seeking classroom and hands-on training for all-hazards incidents should consider attending the FEMA Center for Domestic Preparedness in Anniston, Alabama. Residential courses specific to CBRNE/WMD incidents, to name a few, include “Emergency Medical Operations for CBRNE Incidents,” “Healthcare Emergency Response Operations for CBRNE Incidents,” and “Hospital Emergency Response Training for Mass Casualty Incidents.” Training is fully funded for local, state, tribal, and territorial responders.

Closing

CBRNE/WMD incidents are high-risk, low-frequency events requiring significant planning, training, and coordination across all critical infrastructure. Given the threat of these types of incidents, evaluation of these plans and protocols should be appropriately prioritized. The versatility and increasing portability of POCUS may render it an invaluable resource in MCIs secondary to CBRNE events. Thus, POCUS should be considered in the initial development or re-evaluation of pre-incident plans.

Call-to-Action

Get Prepared for Mass Casualty/CBRNE Incidents by Becoming Certified in Emergency Medicine POCUS.

Unlock the latest POCUS information at the POCUS World Conference. Register here.

About the Author

Mel Ebeling, BS, is a medical student at the University of Alabama at Birmingham Heersink School of Medicine and an EMT at Fultondale Fire & Rescue. Before matriculating into medical school, they were also trained in the field of Hazardous Materials (HAZMAT) response and are certified as a Tank Car Specialist and Highway Emergency Response Specialist. While fairly new to the field of ultrasound, Mel is in the process of becoming POCUS-certified and hopes to integrate this knowledge into their desired specialty: Emergency Medicine. In their free time, Mel enjoys martial arts, pyrography, and serving the community.

Mel Ebeling, BS, is a medical student at the University of Alabama at Birmingham Heersink School of Medicine and an EMT at Fultondale Fire & Rescue. Before matriculating into medical school, they were also trained in the field of Hazardous Materials (HAZMAT) response and are certified as a Tank Car Specialist and Highway Emergency Response Specialist. While fairly new to the field of ultrasound, Mel is in the process of becoming POCUS-certified and hopes to integrate this knowledge into their desired specialty: Emergency Medicine. In their free time, Mel enjoys martial arts, pyrography, and serving the community.

References

- Pazzanese C. Russia’s remaining weapons are horrific and confounding. The Harvard Gazette. Published March 23, 2022. Accessed June 18, 2022. https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2022/03/harvard-analyst-assesses-chemical-weapon-threat-posed-by-russia/

- Reed-Schrader E, Hayoun MA, Kropp AM, Goldstein S. EMS Weapons Of Mass Destruction And Related Injury. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; July 22, 2021.

- 18 USC § 2332a(c)(2). Accessed June 18, 2022. https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/USCODE-2011-title18/USCODE-2011-title18-partI-chap113B-sec2332a/summary