By Victor V Rao MBBS, DMRD, RDMS

Pericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade are serious medical conditions that can have significant implications for a patient’s health and wellbeing and if uncorrected could potentially lead to death of the patient if cardiac function is seriously impaired. In this blog article we will briefly review the above-mentioned conditions and learn how POCUS users can confidently diagnose pericardial effusion and recognize pericardial tamponade pathophysiology and take immediate corrective measures to save the patient’s life.

In the general adult population, data from the Framingham cohort suggests that pericardial effusion may be present in up to 6.5% of individuals. However, the incidence of cardiac tamponade in the US is only about 5 cases per 100,000 population. So, the chances of a clinician encountering a case of cardiac tamponade is not too high.

When you do encounter a patient with cardiac tamponade, you will be instrumental in saving that patient’s life if you are able to diagnose the condition and take appropriate action. If you are in the emergency room, there may be a higher probability of encountering cardiac tamponade patients especially after trauma to the chest. There is a lack of global data on deaths due to cardiac tamponade. A recent study of 254 patients with pericardial effusion found that 44% of their study subjects developed tamponade.

What is a Pericardial Effusion

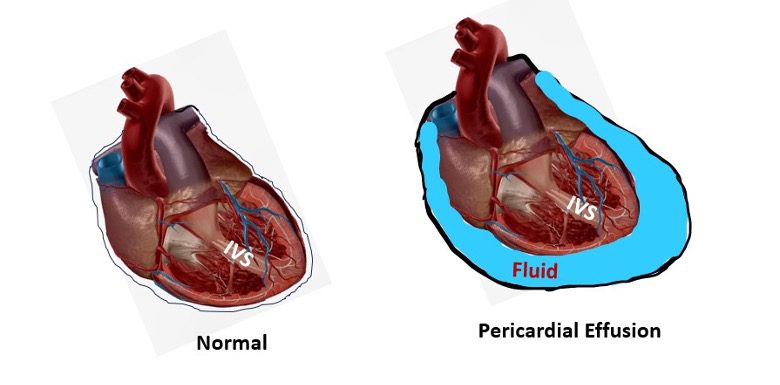

Pericardial effusion refers to the abnormal accumulation of fluid in the pericardial sac, which is the volumetric potential space between the two layers of the pericardium. There is generally a small amount of physiological fluid (15-50 mL) in this space, which acts as a lubricant as the heart chambers contract and relax. The small amount of physiological fluid in the pericardial sac is not visible in most patients using B-mode ultrasound. However, when excess fluid accumulates, it is visible on B-mode ultrasound.

The pericardium has some elasticity, allowing it to stretch slightly to accommodate increased fluid volume. However, if the fluid accumulates rapidly and the elastic limit is reached, even small increases in fluid volume can cause a rapid rise in intrapericardial pressure (>15 mm Hg). The first chambers to be affected will be the venous side of the heart as the pressure on the right side is lower than the left heart. It is important to understand that a patient can go into cardiac tamponade with a relatively small amount of pericardial fluid that accumulated rapidly within a few hours or days.

There have been cases where a large amount of pericardial fluid accumulated over several months or years and the pericardium had time to stretch and did not result in cardiac tamponade. The largest reported pericardial effusion linear dimension without tamponade is 16 cm. The cardiac tamponade physiology is pressure dependent and not volume dependent. It is directly dependent on the rate of fluid collection and the elasticity of the pericardial sac. One patient was reported to have had a chronic massive pericardial effusion for over 10 years without any evidence of cardiac tamponade. Be aware that even a small pericardial effusion measuring as low as 150 ml can lead to cardiac tamponade if it collects rapidly.

Anatomy

The pericardium is a protective, double-walled sac that surrounds the heart and the roots of the great vessels. The pericardium consists of two main layers, the outer fibrous pericardium and the inner serous pericardium. The fibrous pericardium is composed of dense connective tissue and is relatively inelastic and non-distensible in an acute setting. However, in a chronic pericardial effusion it does stretch quite significantly. It helps fix the heart in the mediastinum.

The serous pericardium is composed of two components. They are the parietal layer and the visceral layer. The parietal layer covers the inner surface of the fibrous pericardium. The visceral layer covers the surface of the heart and proximal segments of the great vessels arising from or entering the heart. The pericardium protects the heart and prevents excessive cardiac dilatation. The pericardium also acts as a physical barrier to prevent infection from the mediastinum or chest cavity from spreading to the heart.

Figure 1. Normal heart on the left with no pericardial effusion. Diagrammatic representation showing a large pericardial effusion (blue – fluid) on the right surrounding the heart in the pericardial sac.

Common Causes of Pericardial Effusion

Pericardial effusion can result from various causes, including:

- Infections (viral, bacterial, fungal)

- Autoimmune disorders (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, lupus)

- Cancer (primary or metastatic)

- Mechanical complications of myocardial infarction (MI)

- Uremia in kidney failure

- Hypothyroidism

- Trauma or injury to the heart or cardiac interventions

- Aortic dissection

- Certain medications

Diagnosis of Pericardial Effusion

Diagnosis of pericardial effusion typically involves a combination of clinical assessment and imaging studies.

Clinical Observation/Assessment

Signs and symptoms:

- Chest pain or pressure

- Dyspnea especially during physical activity

- Cough

- Tachycardia

- Palpitations

- Muffled heart sounds

- Dizziness

- Fatigue

- Anxiety or confusion

- Pericardial frictional rub

- Dysphagia

- Hoarseness of voice

- Hiccups

- Jugular venous distension

- Ewart’s sign – dullness to percussion below the level of angle of scapula – due to left lung compression

- Hepatosplenomegaly (sometimes)

Imaging Studies

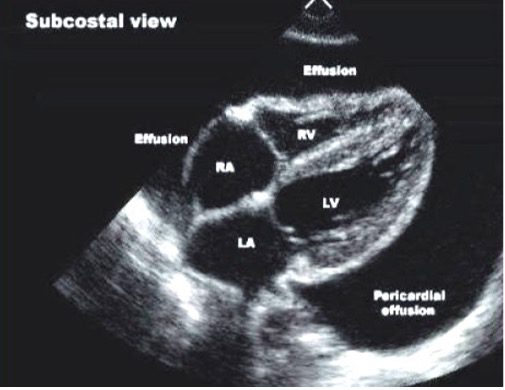

Echocardiography:

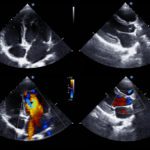

This is the gold standard for diagnosing pericardial effusion. It can visualize the pericardial effusion and assess its size and effect on cardiac function. See figure below.

Figure 2. Large pericardial effusion seen on a subcostal/subxiphoid view of the heart. Note that even though the pericardial effusion is quite large, the right heart chambers are not collapsed.

How to Measure Pericardial Effusion on Echocardiography

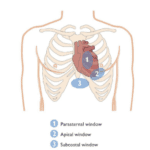

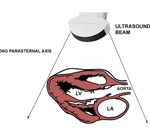

The measurement can be performed on multiple standard echocardiography views such as parasternal long axis, parasternal short axis, apical 4-chamber and subcostal views. Identify the anechoic space between the visceral pericardium (epicardium) and the parietal pericardium. Record the shortest distance in the largest fluid pocket.

Based upon pericardial effusion measurement we can classify pericardial effusions as follows:

| Measurement of Pericardial Effusion | Approximate Volume of Fluid |

| <5 mm | 50-100 ml (minimal) |

| 5-10 mm | 100-250 ml (small) |

| 10-20 mm | 250-500 ml (moderate) |

| >20 mm | >500 ml (large) |

Table 1. Pericardial effusion measurement and corresponding fluid volume and grading. Note that some experts use a different method to grade effusion to small (10 mm), moderate (10-20 mm) and large (>20 mm). It is important to remember that a patient can have a large pericardial effusion with no tamponade or a small pericardial effusion with tamponade. It is more important to observe the right heart chambers and other findings mentioned below.

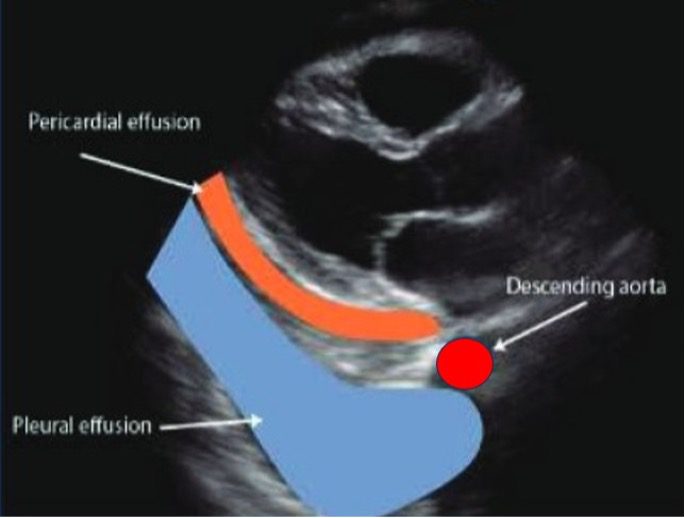

Figure 3. Pericardial effusion versus pleural effusion. A small pericardial effusion and a large pleural effusion seen on a PLAX view. Note that the pericardial effusion is wedged between the descending aorta and the left atrium. The pleural effusion extends posterior to the descending aorta (red).

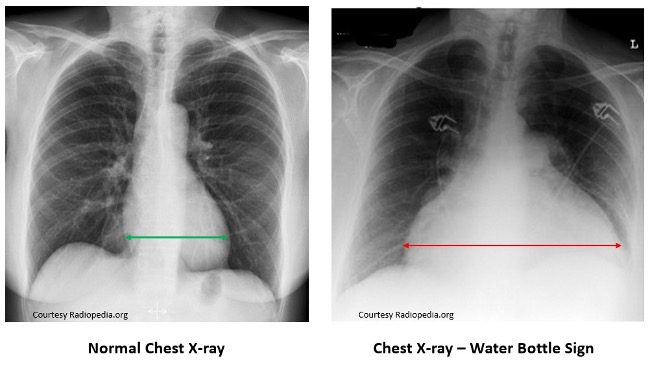

Chest X-ray:

Large effusions may cause an enlarged cardiac silhouette. Unfortunately, a chest X-ray cannot be used to conclusively diagnose a cardiac tamponade. Common signs of a pericardial effusion on a chest X-ray are:

- Water Bottle Sign – Heart’s outline appears enlarged and globular

- Widening of carinal angle – the angle between the left and right main bronchi widens (normal angle is approximately 60 degrees with a range of 40 to 80 degrees)

- Widened mediastinum shadow and enlarged cardiothoracic ratio

Figure 4. Normal chest X-ray on the left with normal cardiac silhouette. The image on the right shows a large, dilated heart silhouette. Water bottle sign – heart silhouette is enlarged significantly and appears like a large water bottle. The carinal angle is also enlarged. C:T ratio is also increased. If you see this finding on a patient immediately proceed to do an echocardiogram to rule out cardiac tamponade.

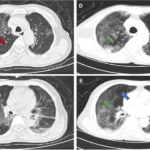

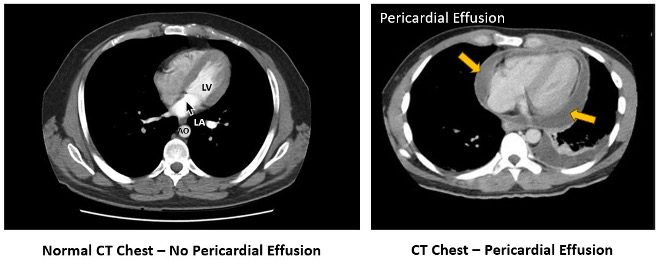

CT scan:

CT scan can provide detailed images of the heart and pericardium and surrounding structures.

Pericardial effusion is visible as a fluid density around the heart. You can also see other findings such as pericardial thickening, flattening of the anterior surface of the heart (right cardiac chambers), bowing of the interventricular septum (due to high intrapericardial pressure), and enlarged vena cava.

Figure 5. The image on the left shows a normal CT chest with a normal heart and no pericardial effusion. The image on the right shows evidence of pericardial effusion.

MRI:

Figure 6. MRI four chamber view of the heart shows a large pericardial effusion (arrows).

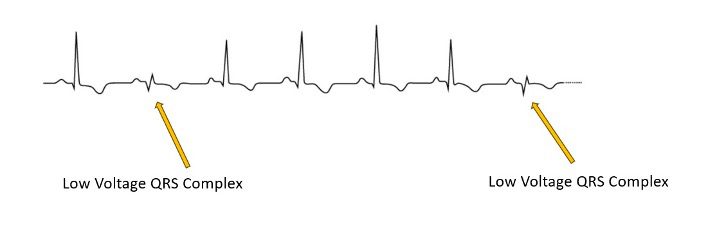

Electrocardiogram (ECG/EKG):

EKG shows low voltage QRS complex or electrical alternans in large pericardial effusions. A large effusion may have the risk of cardiac tamponade. It is important to remember that EKG changes alone are not diagnostic but highly suggestive of a large pericardial effusion. A cardiac echocardiogram must be performed to look for evidence of a pericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade.

Figure 7. Observe the electrical alternans on the EKG tracing. When the heart is swinging in a large pericardial effusion the QRS displays low voltage when the heart is further away from the EKG electrical leads.

Cardiac Tamponade

Cardiac tamponade is a life-threatening condition that occurs when the accumulation of fluid in the pericardial space is sufficient to compress the heart and impair its ability to fill with blood. This leads to a reduction in cardiac output and can result in circulatory collapse if not promptly treated.

Pathophysiology of Cardiac Tamponade

As the fluid accumulated in the pericardial sac, it leads to impaired ventricular relaxation and filling. As more fluid collects, the pericardial pressure increases further to exceed ventricular filling pressure leading to reduced cardiac output. In the final phase the pericardial and left ventricular filling pressures equalize resulting in further reduction of cardiac output.

The increased pericardial pressure results in reduced ventricular filling, decreased stroke volume. Compensatory tachycardia may occur to maintain cardiac output. The compression of right atrium and right ventricular collapse occurs. Blood starts to accumulate in the venous circulation and left ventricle size is further reduced.

Signs and Symptoms of Cardiac Tamponade

The classic presentation of cardiac tamponade was described by Beck’s triad. The three components of Beck’s triad are:

- Hypotension

- Distended neck veins (increased jugular venous pressure)

- Muffled heart sounds

Other signs and symptoms may include:

- Dyspnea

- Chest pain

- Tachycardia

- Pulsus paradoxus (exaggerated decrease in systolic blood pressure during inspiration)

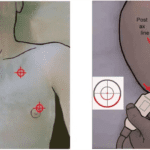

Diagnosis of Cardiac Tamponade (Echocardiography)

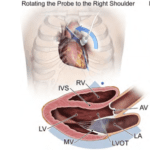

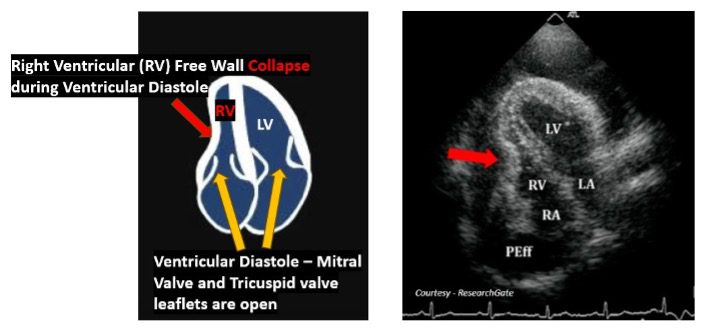

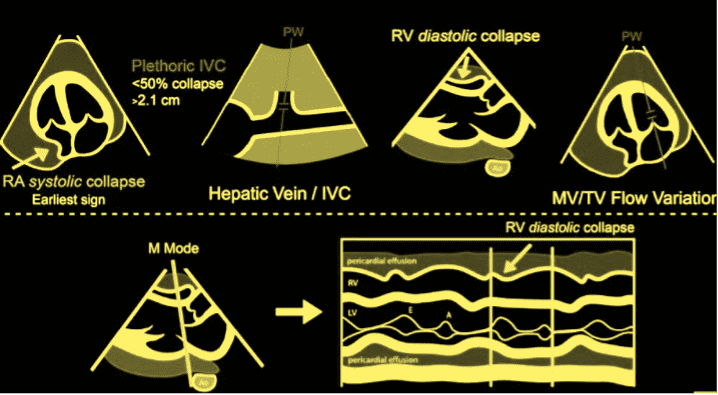

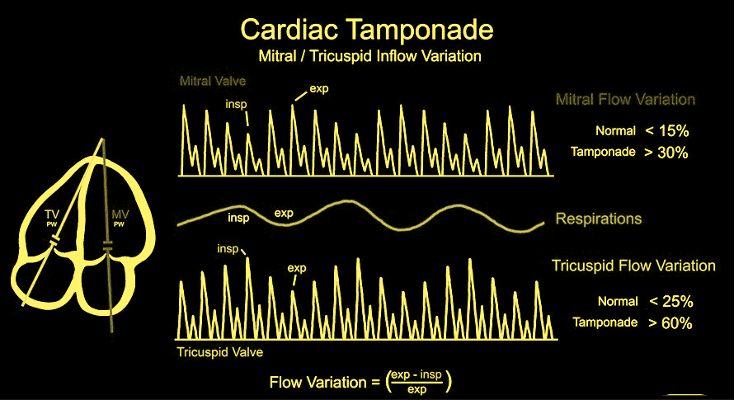

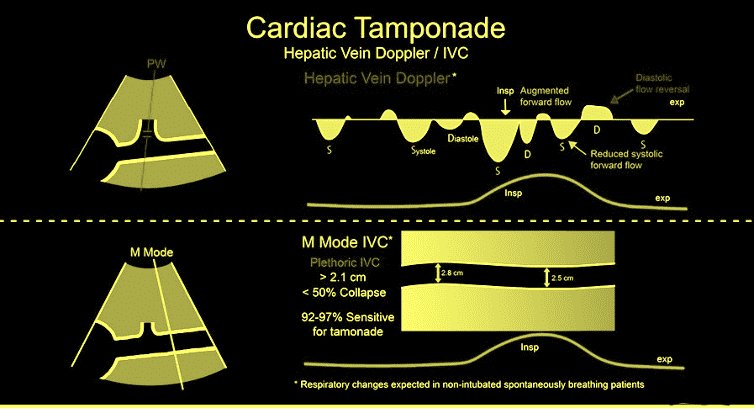

Echocardiography is the primary tool for diagnosing cardiac tamponade. Key findings include the following:

- Diastolic collapse of the right ventricle (sensitivity is 93%, specificity is 100%)

- Late diastolic collapse of the right atrium (earliest sign of tamponade physiology) – sensitivity is 100%, specificity is 82%

- Swinging motion of the heart (large effusion)

- Dilated/plethoric inferior vena cava with minimal respiratory variation

- Respirophasic variation of flow in the mitral valve (>25%) and >40% in tricuspid valve

Figure 8. Diastolic collapse of the right ventricle. This is an early sign of cardiac tamponade. It indicates that the intrapericardial pressure is transiently exceeding the right ventricle filling pressure during ventricular diastole. You may also use M-mode to document the RV free wall collapse in the Parasternal Long Axis (PLAX) view of the heart. Make sure that the atrioventricular valve is open.

Figure 9. Graphic display showing findings of cardiac tamponade. Note that the earliest sign of tamponade physiology setting in is right atrium (RA) systolic collapse. During systole, the atrioventricular valves will be closed as shown in the diagram in the left upper corner. Diagram courtesy of ACEP.

Figure 10. Mitral valve and Tricuspid Valve inflow variation. Diagram courtesy of ACEP.

Figure 11. Cardiac Tamponade – Hepatic vein Doppler and IVC findings. Diagram courtesy of ACEP.

Management of Pericardial Effusion and Cardiac Tamponade

The management approach depends on the severity of the effusion and the presence of tamponade. Small asymptomatic effusions without evidence of tamponade physiology may be managed conservatively with treatment of the underlying cause. Large effusions or tamponade require urgent pericardiocentesis. Recurrent effusions may require more definitive interventions such as pericardial window creation or pericardiectomy.

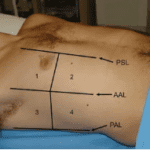

Pericardiocentesis

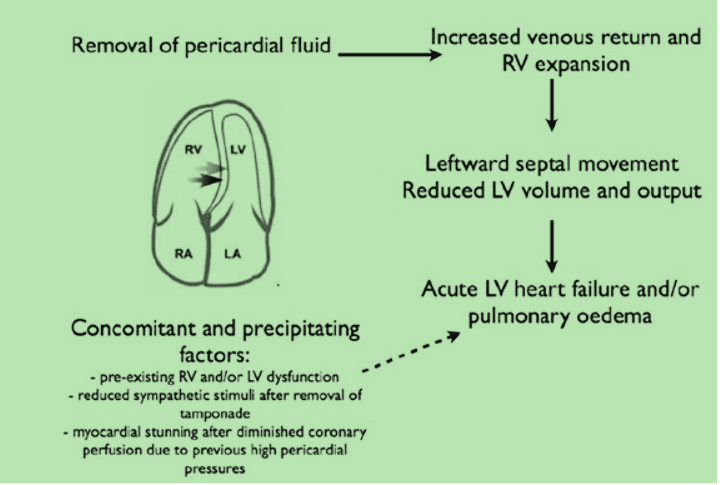

Pericardiocentesis is the procedure for draining fluid present in the pericardial sac. It is best performed under ultrasound guidance. It is generally safe when performed by an experienced physician. It does have potential risks of cardiac puncture, arrhythmias, coronary artery puncture, hemothorax, pneumothorax and hepatic injury when using a subxiphoid approach. Be aware of pericardial decompression syndrome (PDS) following pericardiocentesis. Even though it is a rare complication, we must be aware of it. The exact mechanism is not well understood. It would be safer to remove up to 1 liter of pericardial fluid at a time with close monitoring of the patient up to 48 hours following the procedure.

Figure 12. Cardiac decompression syndrome mechanism following pericardiocentesis. Courtesy Massimo Imazio and Gaetano Maria De Ferrari doi.org/10.1177/2048872620939341

Final Thoughts

Pericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade represent a spectrum of pericardial disease with potentially serious consequences. Prompt recognition and appropriate intervention are crucial for a good patient outcome. Even though a small fraction of patients may develop cardiac tamponade it is a good idea to be able to recognize this clinical condition. My hope is that every clinician around the world will learn this life saving skill and save lives by timely diagnosis and intervention. In a large pericardial effusion or tamponade remove the fluid up to 1Liter at a time and consider gradual decompression.

References