1/19/18

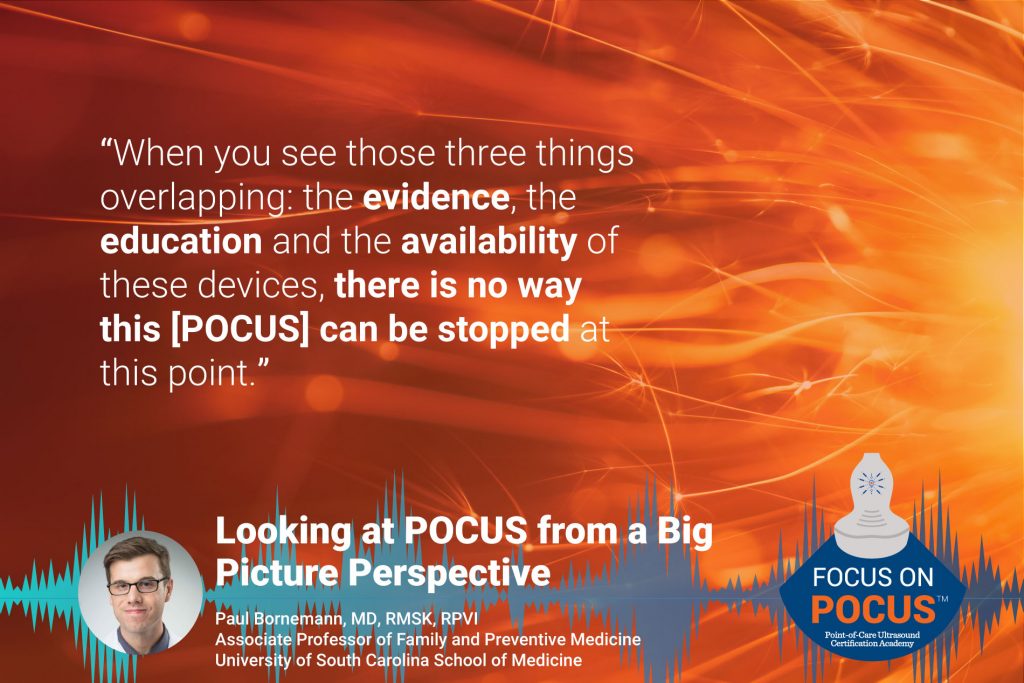

Listen as Paul Bornemann, MD, RMSK, RPVI, Associate Professor of Family and Preventive Medicine, University of South Carolina School of Medicine, reflects on the Big Picture Perspective for POCUS and how Point-of-Care Ultrasound for Primary Care and Family Medicine is transforming the practice regardless of whether people want it to or not.

Listen as Paul Bornemann, MD, RMSK, RPVI, Associate Professor of Family and Preventive Medicine, University of South Carolina School of Medicine, reflects on the Big Picture Perspective for POCUS and how Point-of-Care Ultrasound for Primary Care and Family Medicine is transforming the practice regardless of whether people want it to or not.

Interested in point-of-care ultrasound training? The Generalist Certification education bundle provides POCUS training and certification for primary care and family medicine physicians.

Looking for additional inspiration? Sign up for our POCUS Post™ newsletter to receive monthly tips and ideas.

Engage the community at the POCUS World Conference! Register here.

Transcription:

James Day: Hello and welcome to the Point-of-Care Ultrasound Certification Academy Podcast where we focus on POCUS. Here, we will discuss all things related to point-of-care ultrasound, the practice, the trends, and its impact on healthcare. Our program will engage thought leaders who are defining global patient care with the stethoscope of the future.James Day: James Day, live from the Focus on POCUS studios. Today, we have Dr. Paul Bornemann as our honored guest. Paul H. Bornemann is currently associate professor of family and preventive medicine, program director of the family medicine residency program and director of primary care ultrasound at the University of South Carolina School of Medicine. Dr. Bornemann is board certified in family medicine and has RMSK and RPVI certifications from APCA. He has experienced introducing point-of-care ultrasound curricula in family medicine residency programs, has multiple publications on the topic, and teaches it regularly at national conferences.

James Day: How are you today, Paul?

Paul Bornemann: James, it’s great to be here. Thanks for having me on.

James Day: I’m so glad to have you here today. I know that what’s going on right now is the Family Medicine Experience. The convention is in New Orleans this year, and I noticed there was a POCUS interest group providing workshops that you had a big hand in creating. Do you want to talk about that?

Paul Bornemann: Yeah. Yeah, that’s right. Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to make it down there myself, but the sight of POCUS in the… nationally in the family medicine world has really been growing over the past few years. We started with a member interest group in 2016, and it’s grown to over… I think, we have, last I checked, over 350 members, and one of the things that came up at the FMX, the national convention, two years ago was a Congress of Delegates’ resolution was passed asking the AAFP to formally provide more CME education in the area of point-of-care ultrasound and also asking that the residency programs, it’s a non-binding resolution, but asking that residency programs all incorporate point-of-care ultrasound in their training.

Paul Bornemann: From there, we’ve made a lot of progress in incorporating more CME programs relating to point-of-care ultrasound into the American Academy of Family Physicians’ CME offerings, and they have several per year, national level CME conferences on different topics, and we’ve been able to incorporate the point-of-care ultrasound into a lot of them through some of the members of the point-of-care ultrasound member interest group and then also just other faculty who have been interested in helping to pioneer point-of-care ultrasound in family medicine and primary care.

James Day: That’s great, because I know it’s been a battle for many years. I’ve heard about integrating POCUS into a medical school curriculum and trying to fit it into an already stuffed curriculum. That’s good stuff. I’m happy to hear that. Why is the POCUS movement important for primary care in medicine?

Paul Bornemann: The way I look at it is from a big-picture perspective. In the United States, if you look at the way the healthcare systems run right now, we spend more money per capita, per patient, per percent of our GDP than any other industrialized country. It’s 17% now, I think. A percent of our GDP of all the economy is spent on healthcare. The next closest industrialized country is France, and they only spend 12%, and what do we get in return for that?

Paul Bornemann: If you look at some of the outcomes, we have the lowest life expectancy, highest infant mortality, highest chronic disease burden, so we’re spending a lot of money and we’re not getting a whole lot for it, and there’s probably lots of reasons that we could delve into why that is, but one of them, at least a contributing factor, is that we do spend a lot of money on diagnostic testing. We, in the United States on average per 100 people do 10 MRIs and 24 Cts. That’s out of the general population, out of 100 people, 24 CTs, 10 MRIs, and that’s more than twice the next closest industrialized country, so, again, so we’re spending a lot more money. We’re doing a lot more testing, and it’s not getting us better outcomes, so it’s not to say that spending more, doing more testing is really a better way to do things. It’s just costing more money and not really providing what we’d hope it would.

Paul Bornemann: I think that’s where point-of-care ultrasound comes in, not that it would replace that testing, but one of its most valuable uses is that it can be used to triage patients and figure out which ones may need further testing and which ones you can reassure yourself that there’s not something serious going on, that you can treat them conservatively at least initially, and there’s good data coming out now to back that up.

Paul Bornemann: There’s been a study that came out from the New England Journal of Medicine in 2015 where they looked at using ultrasound to triage patients that came to the ER with suspected kidney stones, and they found that, whether the radiologist did the ultrasound or whether an emergency room doctor did it, they were able to decrease the amount of CTs by 50%, and that’s by using ultrasound first, a limited protocol to triage patients to getting a CT or not, and the outcomes were just the same. With either group, they did just as well, but they were able to decrease the cost, decrease the number of CTs and, of course, decrease the radiation to the patients.

Paul Bornemann: There’d been similar studies that looked at MSK injuries and the number of MRIs that were ordered and looking at when ultrasound could have been used instead. There was a big study in 2010 that found that probably almost half of the MRIs that were ordered in one health system could have been replaced by ultrasound initially and saved potentially billions of dollars over the course of the time period they were looking at.

Paul Bornemann: Additionally, if you look at procedures and the way that ultrasound now has been shown to decrease the rate of complications in a lot of different procedures like central lines, which are done very commonly in hospitals. Almost any procedure where we’re putting a needle into a patient, there’s data that using ultrasound guidance can help decrease complications and, of course, if you decrease complications, you’re doing a better service to the patient and you’re also decreasing cost to the system, so, in some ways, there’s a lot of data that ultrasound can help triage patients and for who would need further testing and help decrease the complications of procedures.

Paul Bornemann: There’s more and more data coming out now that these point-of-care applications can be done by nonspecialist, it doesn’t require doing an entire residency training to do these specific protocols, and I think us in primary care have a lot of potential to build upon the ground that really has been broken, the trails that have been blazed by some of the other pioneering specialties like emergency medicine who back late ’80s, early ’90s started with the FAST scans, the Focused Abdominal Sonography in Trauma, and then, from there, really built upon the toolbox for different point-of-care ultrasound protocols.

Paul Bornemann: I think the exciting thing for us in primary care now that we’re just starting to get into the world that they created is that almost all of those applications in emergency medicine in trauma have some room in primary care, too. They have some application, but then there’s also lots of other areas yet to be discovered that we’re just now starting to think about in primary care to where we could use point-of-care ultrasound for applications that really haven’t been thought about before, like managing chronic diseases like heart failure, hypertension, screening for AAAs, things like that which are more of a chronic care, preventative care sort of application of point-of-care ultrasound, which is really brand new, and I think that gets back to some of the reasons why this is a really exciting thing in primary care now and really starting to take off on a national level for us.

James Day: That’s great. Back to your point, I remember with the IJ cannulation, before it was a standard of care, it was done anatomically, and I think, the hospital that I was at, we averaged about two medical mistakes a month, and after we made all the residents during residency orientation and used the simulation center and the old Blue Phantom task trainers and ultrasound-guided IJ insertion, in one year, we had none, so it was pretty exciting.

Paul Bornemann: I think it also increases the availability of these procedures. For example, in our clinic now, with ultrasound guidance, we feel a lot safer about doing outpatient procedures like paracentesis or thoracentesis, which, in the past, those patients would have to go to the emergency room to get it done, but we have some patients with chronic conditions who need a paracentesis or thoracentesis every week, every other week, and they were having to go to the emergency room and wait around for hours every time, but now that we can do it so safely with ultrasound, we feel very comfortable just having them come into our outpatient clinic and get it done there on a regular basis, which is really better for everybody.

James Day: Yeah. Awesome. That’s awesome. I know everybody’s in the game now, and we did have our emergency room brothers and sisters pioneer in this some time ago, and I want to ask you, so do primary care providers, do they need to worry about stepping on the toes of specialists, radiologists, cardiologists and such?

Paul Bornemann: Yeah, I think that’s a great question because that is a concern I think of a lot of primary care doctors, and maybe one of the reasons why they have some trepidation about learning ultrasound or going into that area, but I think it gets down to if you really look at what the definition of POCUS or point-of-care ultrasound, what it really is, and, for me, I think of it as a focused exam that’s performed at the bedside, so we’re not doing a complete assessment of the entire abdomen or heart, but we’re really doing something focused by the clinician who’s taking of the patient at the bedside of the patient and directed to asking a specific question, preferably an evidence-based protocol or question that they can use to then diagnose or treat the patient or perform a procedure, but they’re… while they’re taking care of the patients so it gives them real-time feedback, answer the question in real time that allows them to change the way they’re taking care of that patient and provide better care.

Paul Bornemann: It’s really not something that I would see ever taking the place of specialists who do the more comprehensive exams such as radiologists or cardiologists, and I think there may still be some concern about turf and I think some specialists may have concerns, too, but the other thing that I’d say is I think that the idea of point-of-care ultrasound, it’s a tidal wave that’s coming regardless of whether people want it to or not.

Paul Bornemann: First of all, again, I’ll reiterate that I don’t think it’s replacing anything that the specialists are doing, but my second point is that it’s comping whether people want it to or not, and there’s several reasons for that, and the first is what I had already went into in some detail about the growing evidence about how this can help improve patient care, decrease the cost of care, but also, if you look at medical education now and the medical schools that are teaching point-of-care ultrasound in their curricula, that’s exploded over the past 10, 12 years.

Paul Bornemann: It started with one or two schools back in 2006 or so, and, now, the last time I checked, it’s well over 60 schools that say they have some sort of curriculum, and probably a lot more that do some sort of ultrasound teaching, and these students are all graduating and going into residency programs and specialty programs, a lot of them going into primary care, and they have the skills to do point-of-care ultrasound, and they like it. They’ve learned it. They see how useful it can be and how they can do it, and they want to continue to use that in their specialty when they’re taking care of patients.

Paul Bornemann: We have a lot of providers coming out of school with ultrasound skills and then, at the same time, we’ve seen over the past five, 10 years this explosion of smaller ultrasounds that are less expensive, that are easy to carry around, much more portable and really good quality, and I think, when you see those three things overlapping, the evidence, the education and the availability of these devices, there’s just no way that this can be stopped at this point even if there are some specialties or… not specialties, but probably more individuals who’ll.. who may have some concerns, so I think the key take-home point is really this is coming and we just need to learn how to adopt it into our system so that we can all benefit from it, that specialists, generalists can all work together to provide the best care for the patients, and that’s really what the bottom line is.

James Day: It was some years ago last December, the University of South Carolina had a primary care workshop, and what struck me was everyone in the crowd, most of the physicians, there were some that came as far away as Hawaii, and they had no exposure, and by the end of that weekend, they really had a nice skill level to the point of doing basic protocols with the ultrasound. I was amazed by that, and you were part of that. You taught a couple of stations and did a presentation as part of that. I enjoyed that a lot.

Paul Bornemann: Yeah.

James Day: What’s happening on the national level regarding primary care, and you’ve touched on it, and point-of-care ultrasound, like I guess primary care organizations like the American Academy of Family Physicians and their positions relating to POCUS?

Paul Bornemann: Yeah. Yeah, like I was saying, there’s really been a lot of interest especially over the past few years. I mean, it’s really come from almost nothing to something that’s almost ubiquitous. I remember, when I first started getting interested in ultrasound five years ago, I didn’t know anybody else in primary care who really even knew about what was going on, and I was in the military where there was a lot of operational providers who would be in situations where, potentially, point-of-care ultrasound would be invaluable just because they don’t have other resources.

Paul Bornemann: It went from that to where we are now where almost everybody knows about it and most practitioners are either interested in learning it or starting to learn it, and a lot of residency programs are also starting to incorporate it into their curricula. As I said, in 2016, the Congress of Delegates made the recommendation that all family medicine residency programs start teaching point-of-care ultrasound in their curricula, and later that year, the American Academy of Family Physicians also came out with a POCUS curriculum guideline, which is available online now. If you Google AAFP POCUS curriculum guideline, that document is there and endorsed by the AAFP, so it’s really amazing to me just how quickly this has grown just over the past two to five years and how ubiquitous it is the interest in point-of-care ultrasound now.

James Day: Yeah. A quick story, I remember I was a cardiac sonographer downtown Philadelphia at the Graduate Hospital, and we had a residency program in cardiology, and I actually taught the residents. I go, “Look, you guys can do this. Here’s a button, and here’s a subcostal view. You want to stop calling me. Stop paging me. I don’t want to come in on the weekend,” and I did it out of… for that reason, and then as it went along, they just wanted to learn more and more, and that was probably, golly, ’96, ’97. Yeah.

Paul Bornemann: Yeah. I think one of the biggest barriers initially is just that fear of stepping into an area where you’re not supposed to be. As a doctor or a family medicine doctor, in the past, we didn’t think we should put an ultrasound probe on somebody’s heart because that’s not what we do and we don’t want to step outside our comfort zone, and I think that’s one of the biggest barriers initially is just realizing like, hey, this is something that, under specific circumstances and with the correct training, we can do safely and it can actually improve the care of patients and be really a lot of fun as well.

James Day: Sure. Sure. Listen, Dr. Bornemann, thanks a lot Paul. We really appreciate your taking the time to be here on today’s show, and it’s really an honor to have you on our podcast, and keep doing what you’re doing.

Paul Bornemann: Thank you, James.

James Day: We want to thank you. Thank you so much.

Paul Bornemann: All right, thanks for having me. I really appreciate it.

James Day: All right, buh-bye.

Paul Bornemann: Bye.

James Day: We hope you enjoyed today’s podcast, Focus on POCUS. Be sure to tune in with us next week for more interviews with thought leaders that are on the forefront of global point-of-care ultrasound.