Victor V Rao MBBS, DMRD, RDMS (APCA)

Over three million non-fatal injuries are reported in the U.S. annually, with more than 150,000 resulting in death. Comparatively, yearly, five million deaths occur worldwide due to injuries. In some instances, death may not be preventable due to its serious nature. However, some could. In these cases, individuals died due to a missed or delayed diagnosis of occult injuries and internal bleeding. Measures can be taken to lower morbidity and mortality rates. Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) can play a significant role and make a huge difference by providing clinicians the ability to promptly diagnose occult bleeding or injuries and expedite surgical measures to stop the bleeding.

When a patient is brought to the emergency department (ED) with a history of trauma, it is critical to know the mechanism of injury because that information will help us determine the extent of physical injuries. For example, if the patient was involved in a motor vehicle accident, it is important to know if it was city or highway speed because crashes at high speed may have a more elevated potential for deceleration injury to the aorta, spleen, and liver. A fatal crash at highway speeds with two dead and three injured can indicate that the impaired individual may have serious internal injuries. This scenario would be very different from an accident that occurred within city limits with zero casualties and only one or more injured.

After the initial primary survey of the patient (the C ABCDE protocol), proceed to the secondary survey, which would include a physical exam to look for signs of trauma related to the head, neck, chest, abdomen, and extremities. Remember, a physical exam may not be sensitive enough to detect internal injury or bleeding and can be even more challenging in an unconscious or uncooperative patient. Every clinician needs to answer a question at this stage. “Is there internal bleeding or free air inside the abdominal cavity?”

POCUS effectively answers that question using the eFAST protocol, which a well-trained clinician can perform in under two minutes. The eFAST exam also looks for fluid around the heart, ruling out cardiac tamponade physiology and free fluid in the chest, abdomen, and pneumothorax.

It is important to note that the blood inside the peritoneal cavity may have a variable appearance on ultrasound. Commonly it appears anechoic on ultrasound but could also appear hypoechoic or hyperechoic. Remember to be aware of other pathological conditions which may show anechoic on ultrasound. Hyperechoic blood may be challenging to detect. A retroperitoneal bleed can also be a real challenge to identify on ultrasound. Be cognizant of other potential pitfalls while performing an eFAST exam. Some common pitfalls or challenges are as follows:

- Renal or hepatic cyst misdiagnosed as free fluid

- Perinephric fat misdiagnosed as free fluid in the Morison’s pouch

- Misdiagnose ascites as a positive eFAST exam

- Examining the Morison’s pouch and not examining the region near the tip of the liver may lead to missed diagnosis

- Isoechoic, hypoechoic, or hyperechoic blood missed

- Overlooking free fluid around the spleen

- Missing free fluid due to smaller volumes present in the abdominal cavity

- Missing a cardiac tamponade

- Misdiagnosing ovarian cyst, hydrosalpinx, or physiological free fluid in the pouch of Douglas/cul de sac as blood

- Mistaking seminal vesicles for free fluid in the pelvic cavity

- Missing free air in the peritoneal cavity, incorrectly diagnosing as normal bowel gas

- Failure to perform follow-up/serial ultrasound exams

- Ultrasound is not very sensitive to detect solid organ injury

- Patient’s body habitus can present challenges

- Presence of air pockets in the subcutaneous tissue or the abdominal cavity may cause dirty shadows, preventing adequate ultrasound imaging

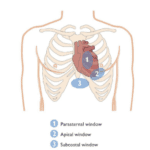

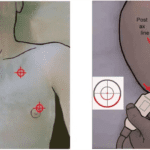

When conducting an eFAST exam, the patient should be scanned in the supine position. A curvilinear low-frequency transducer and a phased array low-frequency transducer are ideal for imaging the heart in additional views if the subcostal view does not yield a good image. Some clinicians prefer to use the low-frequency phased array transducer for the entire exam.

An individual with a history of abdominal or thoracic trauma is a common indication for performing an eFAST exam. The injury could be blunt or penetrating. Another common indication would be a patient who was stable on arrival at the emergency department but has deteriorated over time and become hemodynamically unstable. This would suggest that the patient may have internal bleeding, and an eFAST exam would quickly confirm the diagnosis as hemodynamic instability usually occurs only with significant internal bleed.

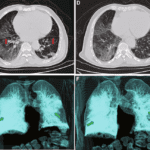

The real value of the eFAST exam is in a positive exam. If we find evidence of internal bleeding and the patient is unstable, they should be sent immediately to the OR for surgical intervention. The objective is to locate the bleeding site and stop it. If the patient is stable, there may be an opportunity to perform a CT scan to look for evidence of organ damage if there is a high index of suspicion. If an eFAST exam is negative, it could mean that the patient has no internal bleed, or they do, but the volume is small and not yet detectable on ultrasound. Below are some examples of a positive eFAST exam.

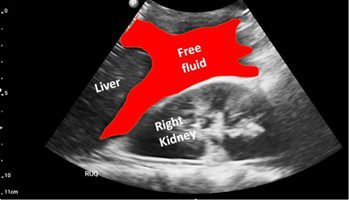

Fig. 1 Right upper quadrant view showing the right lobe of the liver, right kidney, and the potential space between the two (Morison’s pouch – also known as the hepatorenal fossa). A significant amount of anechoic free fluid is seen in the Morison’s pouch. It is vital to understand that the kidney is a retroperitoneal organ. Free fluid or blood in the peritoneal cavity starts to collect at the inferior edge of the liver and then fills into the Morison’s pouch.

Fig. 2 Labeled view of Fig. 1. The image shows the free fluid/blood highlighted in red.

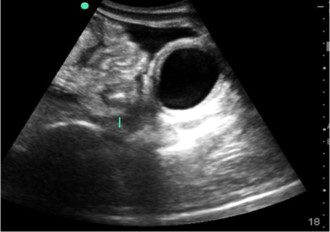

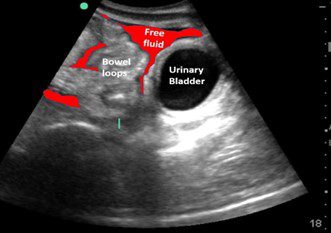

Fig. 3. Transabdominal pelvic view showing anechoic urine in the bladder and anechoic free fluid superior and anterior to the bladder. Bowel loops are also seen.

Fig. 4 Labeled view of Fig. 3 with free fluid indicated in red.

In conclusion, the eFAST exam is instrumental in evaluating trauma patients. Use judiciously and be aware of the pitfalls. Always correlate clinically. Review the patient’s ultrasound images and videos with positive and negative findings to familiarize yourself with the findings in the setting of trauma and develop pattern recognition skills.

The eFAST exam has the potential to save lives. Let no individual die due to an undiagnosed internal bleed. Aim to perform the exam in under two minutes or less with high accuracy and confidence levels. An eFAST exam may not rule out the need for a CT scan. If the patient is stable, a CT scan may also be performed to rule out solid organ injury if it’s suspected.