By Victor V Rao MBBS, DMRD, RDMS

Introduction

Trauma is one of the leading causes of death in individuals less than 45 years old. Approximately 80% of individuals presenting with a history of trauma have blunt trauma and most of the deaths in those patients occur due to hypovolemic shock. 12% of patients with blunt trauma have occult intraperitoneal bleed. Occult intraperitoneal bleed can be detected using POCUS when the amount of intraperitoneal blood is at or above detectable levels for that patient. When assessing a patient with trauma to the trunk you must follow the eFAST protocol. The EFAST protocol is an extended version of the original FAST protocol which was developed by surgeons.

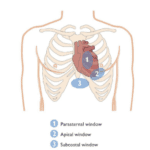

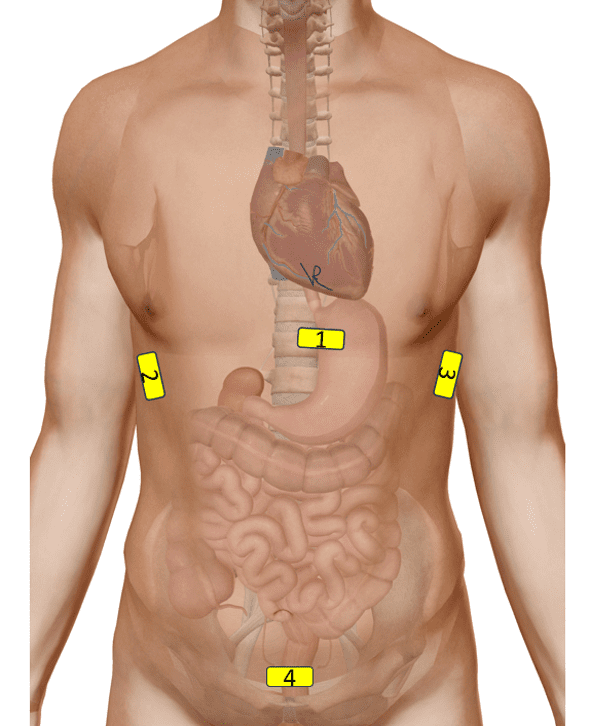

The original Focused Assessment with Sonography in Trauma (FAST) was first published by G S Rozycki et al. in 1998. Ultrasound examination was performed in four regions in the trunk. They were:

- Pericardial sac area (to look for pericardial effusion and tamponade)

- Right upper quadrant (to look for fluid in the Morison’s pouch and right subphrenic space)

- Left upper quadrant (to look for fluid in the splenorenal recess and left subphrenic space)

- Pelvic region (to look for free fluid in the region or around the urinary bladder)

In 2004, A W Kirkpatrick et al. published an article describing the use of ultrasound to diagnose pneumothoraces in trauma patients in addition to the original FAST exam and called it the EFAST examination.

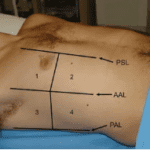

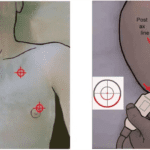

Figure 1. Probe positions for the original FAST examination.

The Morison’s Pouch

In this blog we will focus on Morison’s pouch only. The Morison’s pouch is also known as the hepatorenal fossa and is a potential intraperitoneal space between the right lobe of the liver and the right kidney. The spelling of Morison’s pouch shows different variants and I have chosen the one I like to use and is commonly used in various articles. Some also refer to it as the right subhepatic space. Its boundaries are as follows.

- Right hepatic lobe and the gallbladder anteriorly

- Superior surface of the right kidney along with the right adrenal gland which may not be visible on ultrasound if it is not enlarged due to a pathology, second part of the duodenum, hepatic flexure of colon and the pancreatic head.

- Inferiorly we have the transverse mesocolon.

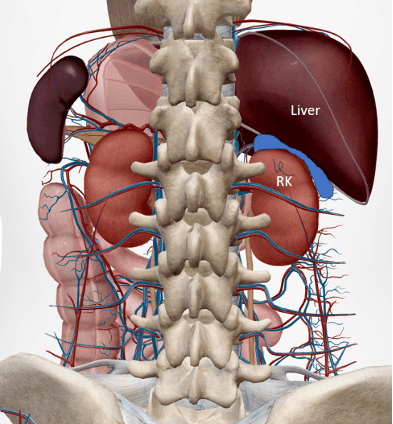

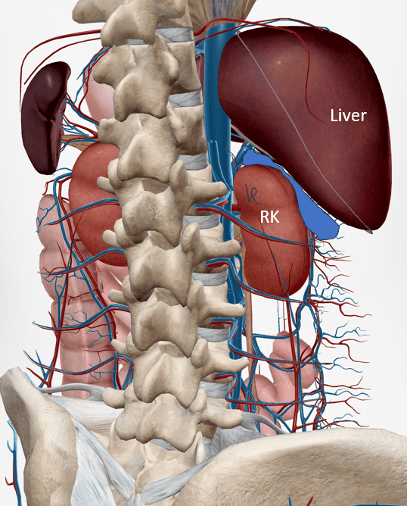

The posterior subhepatic space also communicates with the right paracolic gutters and so we can also look for evidence of free fluid in the paracolic gutters if the volume is significant. Free fluid such as internal bleeding into the abdominal cavity due to trauma or even ascites or some collection inside the peritoneal cavity due to rupture of bowel can have the fluid track down into the Morison’s pouch as it is one of the potential lowest dependent spaces in the peritoneal cavity where the fluid can collect due to gravity if the patient is in the supine position. Below are some anatomical diagrams I put together so you can get a deeper understanding of the Morison’s pouch and its location. It is important to remember that the kidneys are retroperitoneal organs.

Figure 2. Morison’s Pouch is highlighted in blue. Please note this is just a diagrammatic representation to show the location of the Morison’s pouch. Some anatomical structures have been removed to show the right kidney. When no collection is present the space collapses. This view is from the anterior region viewing towards the posterior region.

Figure 3. Morison’s Pouch is highlighted in blue. Please note this is just a diagrammatic representation to show the location of the Morison’s pouch. Some anatomical structures have been removed to show the right kidney. When no collection is present the space collapses. This view is from the posterior aspect.

Figure 4. Morison’s Pouch is highlighted in blue. Please note this is just a diagrammatic representation to show the location of the Morison’s pouch. Some anatomical structures have been removed to show the right kidney. When no collection is present the space collapses. This view is from the right posterior lateral aspect.

How to Assess the Morison’s Pouch with B-mode/ 2-D Ultrasound

Scan the patient with the patient in the supine position. Use a low frequency curvilinear transducer or a suitable low frequency transducer with abdominal or similar preset. Do not raise the head end of the bed or have the patient in the lateral decubitus position as that may displace the fluid. Make sure that the patient has been in the supine position for a few minutes to allow the fluid to gravitate into the Morison’s pouch. Be aware that the value is in the positive exam. If no fluid is detectable make sure to scan more anteriorly near the inferior margin of the right lobe of the liver. If the fluid volume is less and below detectable levels, you can scan in other potential spaces following the EFAST protocol. Consider placing the patient in a Trendelenburg position to increase the sensitivity of detecting free fluid in the Morison’s pouch.

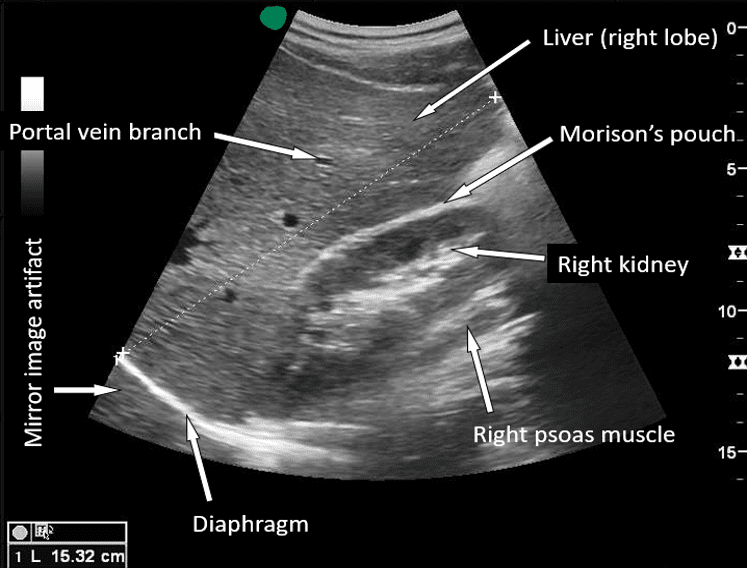

Figure 5. B-mode ultrasound image obtained in the right upper quadrant showing the location of the Morison’s pouch. Keep in mind that it is a potential space. No evidence of free fluid was seen in Morison’s pouch.

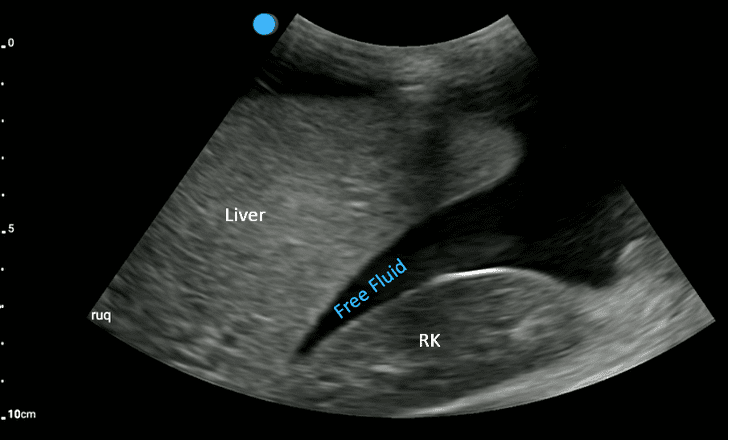

Figure 6. The right upper quadrant view using B-mode/2-D mode shows a significant amount of anechoic free fluid. In the setting of abdominal trauma this is suggestive of intraperitoneal hemorrhage unless ruled out. Compare with the normal image.

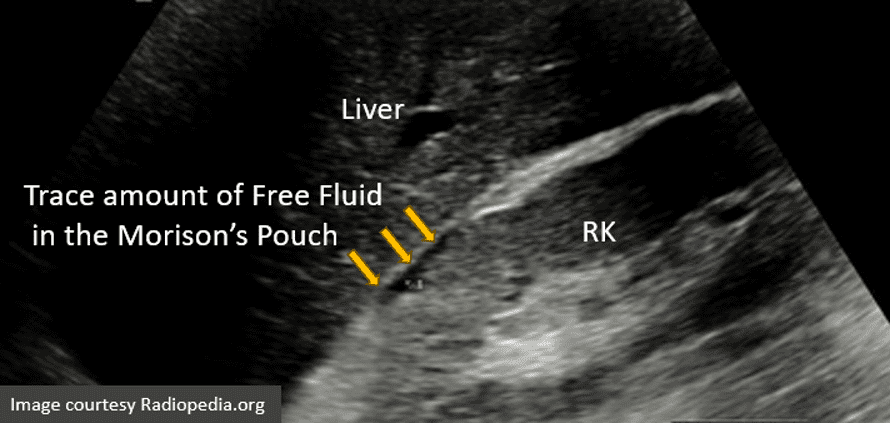

Figure 7. A small amount (trace) of anechoic free fluid seen in Morison’s Pouch (arrows).

Limitations and Pitfalls

Be aware that the sensitivity of ultrasound to diagnose free fluid in the peritoneal cavity is approximately 74-80%. You may see different numbers reported in various manuscripts. If the volume is over 200 mL, then there is a high likelihood for a positive EFAST exam to detect free fluid in the peritoneal cavity. Some studies have reported even a free fluid volume to be as high as 619 mL to be detected using B-mode ultrasound. The body habitus of the patient may be a contributing factor. Some experts even recommend placing the patient in a Trendelenburg position to improve the sensitivity of fluid detection in Morison’s pouch.

Ultrasound cannot differentiate blood from ascites as both may appear anechoic. Some cases of large simple renal cyst or hepatic cyst or even perinephric adipose tissue have been misdiagnosed as occult intraperitoneal bleeding. Always correlate clinically. Not all patients with free intraperitoneal bleeding will require surgical intervention. However, if there is a large volume of intraperitoneal bleeding then surgical intervention is needed. The pelvic cavity and the costophrenic angles have a lower threshold for detection of free fluid in those regions.

Final Thoughts

EFAST examination using B-mode/2-D ultrasound is an excellent modality to examine a patient who has a history of trauma to look for evidence of occult bleed. The value is in a positive EFAST examination. If you suspect that the patient has internal organ trauma then a CT scan must be done to rule it out. Ultrasound may not be sensitive enough to diagnose liver and spleen contusion or injury. Sometimes you may be able to diagnose injury to internal organs with POCUS. A negative EFAST could be due to either a normal case with no internal bleeding or a case in which the amount of blood loss is not yet significant enough to be detected on ultrasound. Ultrasound may not be sensitive enough to diagnose retroperitoneal bleed. Refer for a CT scan and observe the patient closely at regular intervals to make sure the vitals do not deteriorate.

References

- doi: 10.1097/00000658-199810000-00012

- https://www.pocus101.com/efast-ultrasound-exam-made-easy-step-by-step-guide/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1191535/?page=2

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15345974/

- https://tsaco.bmj.com/content/5/1/e000438

- https://www.acep.org/sonoguide/basic/fast