By Victor V Rao MBBS, DMRD, RDMS

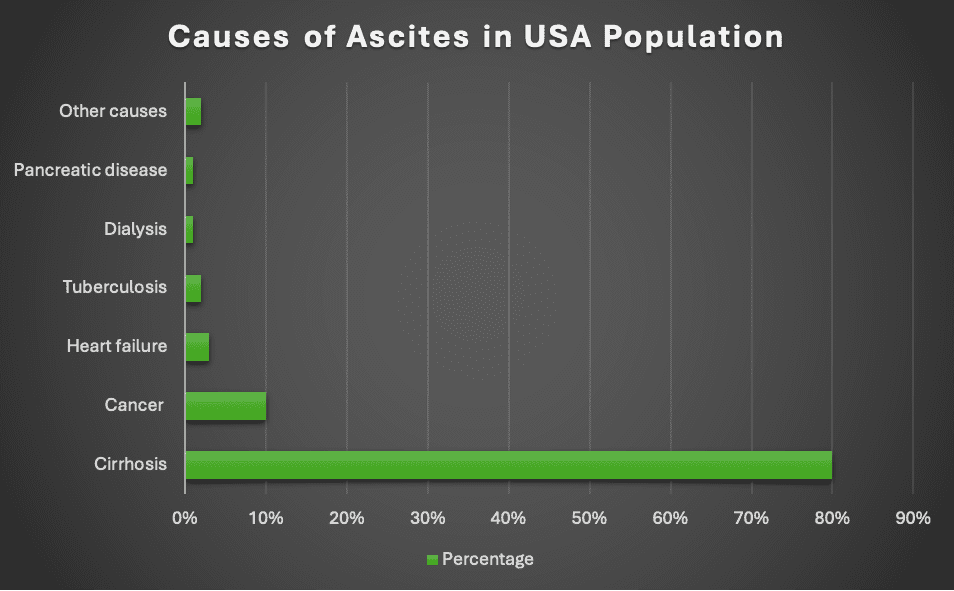

Ascites is defined as a pathological accumulation of ascitic fluid inside the peritoneal cavity. The word “ascites” is derived from the Greek word “askos” which means “bag” or “sac”. It was a name given to a type of ancient Greek pottery or vessel used to pour small amounts of liquids. The most common cause of ascites in the United States is cirrhosis of the liver with associated portal hypertension. There are other causes of ascites such as cancer, heart failure, tuberculosis, dialysis, pancreatic disease and other rare causes. See table below.

Table 1. Causes of ascites in USA. Observe that the most common cause of ascites in the US is liver cirrhosis (also known as hepatic cirrhosis).

Patients with minimal ascites may be asymptomatic. As the fluid volume increases the patient will experience weight gain, increase in abdominal girth, abdominal discomfort and even dyspnea. Abdominal ultrasound is the most used imaging modality to detect the presence of ascites. The advantage of ultrasound is that it can be readily available at the point of care setting. Also, it is a low-cost imaging modality with no unnecessary ionizing radiation exposure risk to the patient. If needed, ultrasound can also be used to guide paracentesis safely to analyze the true nature of the fluid. The ultrasound guided procedure must be done with utmost care to not injure organs or the bowel and must be done with sterile precautions to avoid introducing infection into the fluid that may lead to bacterial peritonitis.

One study reported that physical examination maneuvers alone had a low sensitivity of 50% to 94% and a specificity of 29% to 82%. The overall accuracy of physical examination was reported to be 58%. The study concluded that the only physical examination maneuver with over 90% accuracy is that ascites is absent if no flank dullness is elicited. This itself can be debatable because there could be a small amount of ascitic fluid which may not only be missed by physical examination but also by an ultrasound examination. Ultrasound is more sensitive to detecting free fluid in the pelvic region as compared to the left and right upper quadrants and the paracolic gutter regions.

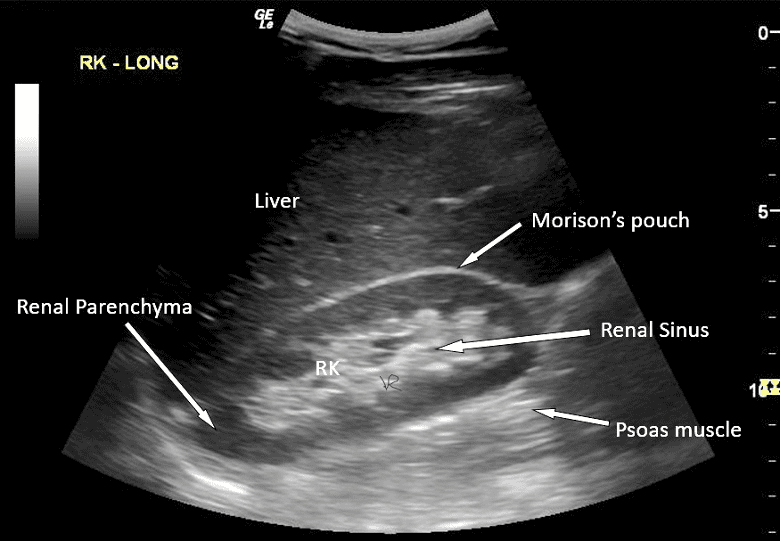

In general, the sensitivity of ultrasound to diagnose free fluid in the peritoneal cavity is approximately 74-80% based on a research study. You may feel confused as to why the numbers are different. The sensitivity is dependent on the volume of fluid and the patient’s body habitus. You may see different numbers reported in various manuscripts. If the volume is over 200 mL, then there is a high likelihood for a positive POCUS examination to detect free fluid in the peritoneal cavity in the region of Morison’s pouch in an average patient. Some studies have reported a free fluid volume to be as high as 619 mL to be detected using B-mode ultrasound in patients who are obese. It is important to be aware that body habitus of the patient can be a significant contributing factor. The value is going to be in a positive examination with clear evidence of anechoic free fluid in the potential spaces inside the abdominal cavity. Some experts even suggest placing the patient in a Trendelenburg position to improve the sensitivity of fluid detection in Morison’s pouch.

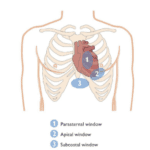

It is recommended to use a low frequency curvilinear transducer to scan the patient’s abdomen using B-mode/2D ultrasound. If a curvilinear transducer is not available, then you may use a low frequency phased array transducer to scan the patient’s abdomen. The patient should be in a supine position. The bed should be horizontal. Adjust the depth setting to approximately 15 to 20 cm or more if needed and scan with the transducer orientation marker pointing cephalad. Place the transducer in the right upper quadrant in the anterior or mid axillary plane and aim the ultrasound beam posteriorly to obtain a view of the Morison’s pouch. You may also scan the left upper quadrant, the paracolic gutters and the pelvic region.

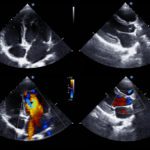

Figure 1. Morison’s pouch view. No evidence of fluid is seen in Morison’s pouch.

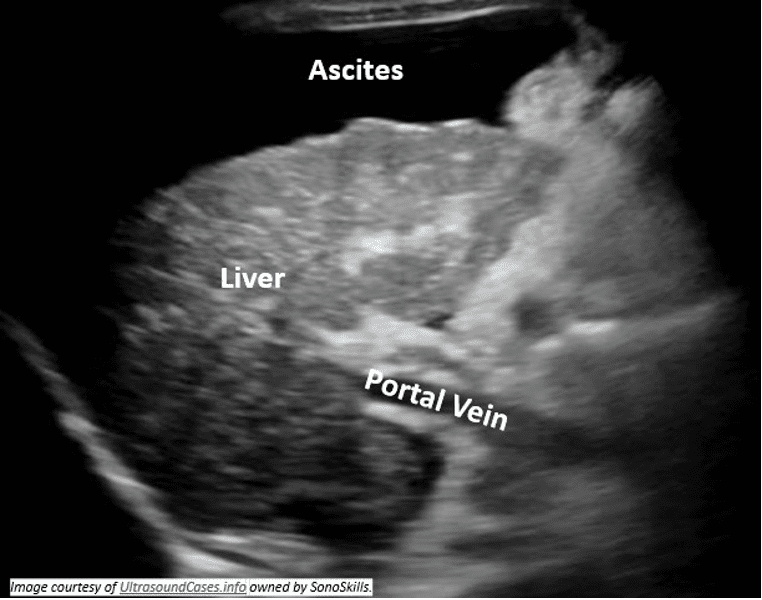

Figure 2. Small shrunken cirrhotic liver with heterogenous echogenicity and nodular surface. Anechoic ascitic fluid is seen surrounding the liver.

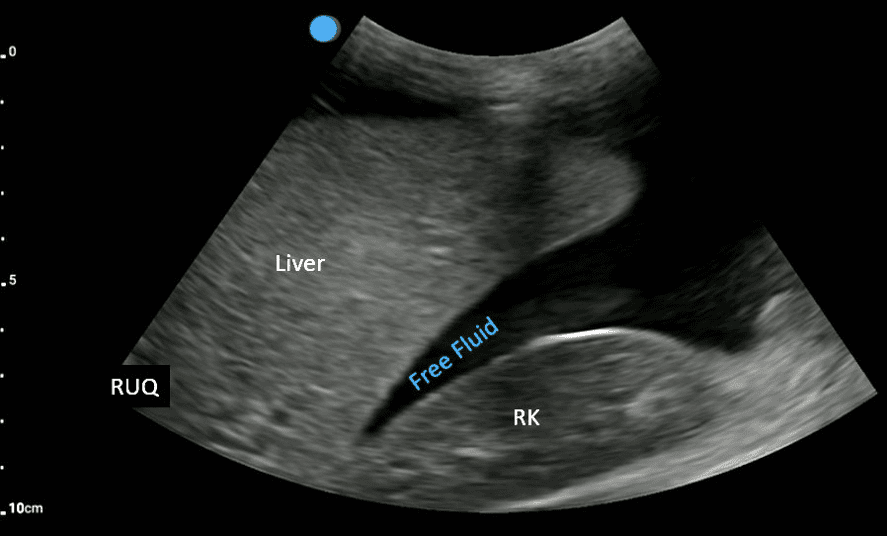

Figure 3. Anechoic free fluid is seen in Morison’s pouch. This patient had a history of trauma and so we suspect the fluid to be blood due to occult internal bleeding. The liver surface is smooth as compared to the image above in Figure 2. To truly know the nature of the fluid an ultrasound guided paracentesis and full analysis of the fluid is recommended. Always correlate clinically.

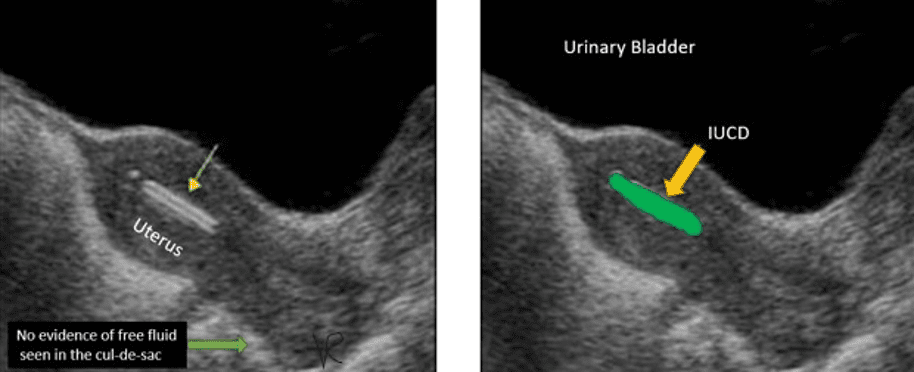

Figure 4. Female pelvic ultrasound mid-longitudinal view of the uterus with a normal posterior cul-de-sac or pouch of Douglas. No anechoic free fluid seen in the posterior cul-de-sac (most dependent location in the female pelvic region. A hyperechoic liner structure is seen in the uterine cavity (IUCD).

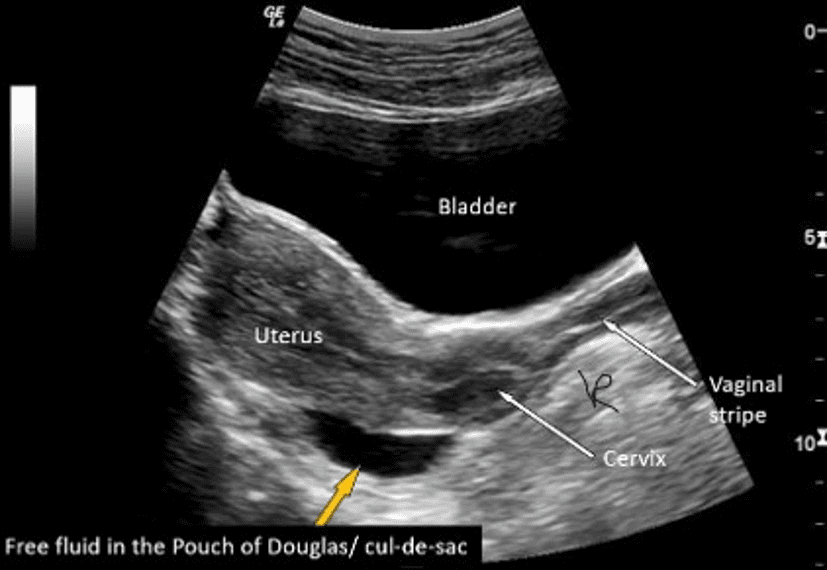

Figure 5. Small amount of physiological anechoic fluid seen in the cul-de-sac (Pouch of Doulas). Males have very little amount of physiological intraperitoneal fluid. Females in the reproductive age group could have normal physiological fluid up to 20 cc depending on the phase of their menstrual cycle.

In conclusion, diagnostic ultrasound is an excellent modality to look for evidence of ascites. You must correlate with the patient’s history and physical examination findings. If ascites is detected, look for common causes of the fluid accumulation. If the fluid volume is adequate and will allow a safe paracentesis under ultrasound guidance, then proceed to withdraw fluid under dynamic ultrasound guidance from the deepest pocket with no bowel loop or organ tissue in the path of the needle. You may also use a static method (not preferred) to mark the deepest safe pocket of fluid if the volume of fluid is huge with 4-5 cm or more deep vertical pocket with no organ tissue such as the liver or bowel loops in the fluid pocket. Do not withdraw more than 1.5 Liters of fluid at a time. Locate the location of inferior epigastric vessels using color or power Doppler and do not injure those vessels during the procedure.

References

https://journals.sagepub.com/eprint/ft77BuRqHqtghaNaT66b/full

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/368603